|

|

The

very heart-beat of music is Laya. Rhythm in Carnatic music is accorded a

very high status as is evident from the Sanskrit maxim, "Layah

pita", meaning, Rhythm is the Father. We shall now explore the

different facets of rhythm in Carnatic music. The

very heart-beat of music is Laya. Rhythm in Carnatic music is accorded a

very high status as is evident from the Sanskrit maxim, "Layah

pita", meaning, Rhythm is the Father. We shall now explore the

different facets of rhythm in Carnatic music.

APPRECIATING LAYA

Rhythm is omnipresent. There is rhythm in the movement of heavenly bodies

just as in the life cycles of micro organisms. It is only natural that man

is endowed with it. Whenever we listen to music, we look for the rhythmic

movements in it and then find ourselves tapping our feet or clapping our

hands or even dancing to it. But what exactly do we mean by rhythm? Rhythm

can be defined as a process in which the nuclei of attention are separated

by individual parts of time. Whenever we listen to music, we cannot but

perceive rhythm. Rhythm gives stability and form to music. It can be

described as the tangible gait of any musical movement. In Carnatic music,

this is referred to as Laya. The common fallacy is that rhythm or laya is

confined to percussion instruments and the rhythmic patterns produced

therein. But laya is not limited to just that. It is present not only in

melodic compositions, which usually have a rhythmic metre in an apparent

manner but also in the creative aspects, sometimes conspicuously (like in

Neraval or Kalpanaswara) and subtly at others (Raga alapana and Tanam).

RHYTHMIC ASPECTS

The rhythmic aspects in Carnatic music are arguably among the most

developed and sophisticated across the world. The patterns range from the

simple to the complex. The study of rhythmic aspects involves

understanding the terms Tala and Laya.

Tala and Laya

Tala is often confused with Laya. Laya refers to the inherent rhythm in

anything. Irrespective of whether it is demonstrated or not, it is always

present. This can be better illustrated with an example. We know that the

sun, the planets and other heavenly bodies are moving objects. Even as our

earth rotates on its axis and revolves around the sun, these bodies have

their own fixed movements and speeds. Even a microscopic disturbance in

that speed may lead to disasters of huge proportions. So laya can be

explained as the primordial orderliness of movements. Expression of laya

in an organised fashion through fixed time cycles is known as Tala. Thus

it serves as the structured rhythmic meter to measure musical

time-intervals. Tala in Carnatic music is usually expressed physically by

the musician through accented beats and unaccented finger counts or a wave

of the hand. In other words, Tala is but a mere scale taken for the sake

of convenience.

THE TALA SYSTEM

The soundness of a system, primarily mathematical in character, consists

of its internal coherency, logical rigidity and numeric accuracy. The tala

system in Carnatic music satisfies all these conditions and is not only

perfect but also beautifully elastic.There are six parts (Angas - limbs) of a tala but the following three

are used more frequently than the others:

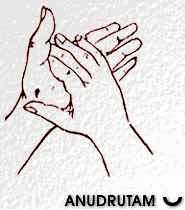

Anudrutam

- a beat, represented by the symbol "U". This is physically

represented as 1 unit.

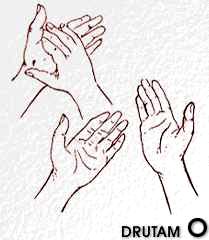

Drutam

- a beat and a wave of the hand, represented by the symbol "O".

This is physically represented as 2 units.

Sankeerna

Laghu

Laghu

- a beat followed by finger counts starting from the little finger. It is

represented by the symbol "l". Laghu can be of five types (Jaati)

depending on the number of units:

Chaturasra (Jaati) laghu has a beat plus

3 finger counts, which is a total of 4 units.

Tisra (Jaati) laghu has 3 units i.e. a beat plus 2 finger counts.

Misra (Jaati) laghu has 7 units, i.e. a beat plus six finger counts.

Khanda (Jaati) laghu has 5 units, i.e. a beat plus four finger counts.

Sankeerna (Jaati) laghu has 9 units, i.e. beat plus eight finger

counts.

To render Misra and Sankeerna laghu, one comes back to the little

finger after exhausting the fingers while counting up to 6.

The remaining 3 angas, namely Guru (8 units), Plutam (12 units) and

Kakapadam (16 units) are not frequently used in the talas generally

used in the concerts. These talas find greater use in the ancient tala

system. In the present day context, they figure in thematic programmes or

Pallavi demonstrations.

An example of a tala that uses all the parts mentioned so far is

Simhanandana tala, the longest tala, with 128 units. Talas make the

counting of larger meters (some of them beyond a hundred units) easier.

The audience also gets an opportunity to participate more actively in the

concert when they maintain tala along with the performers.

|